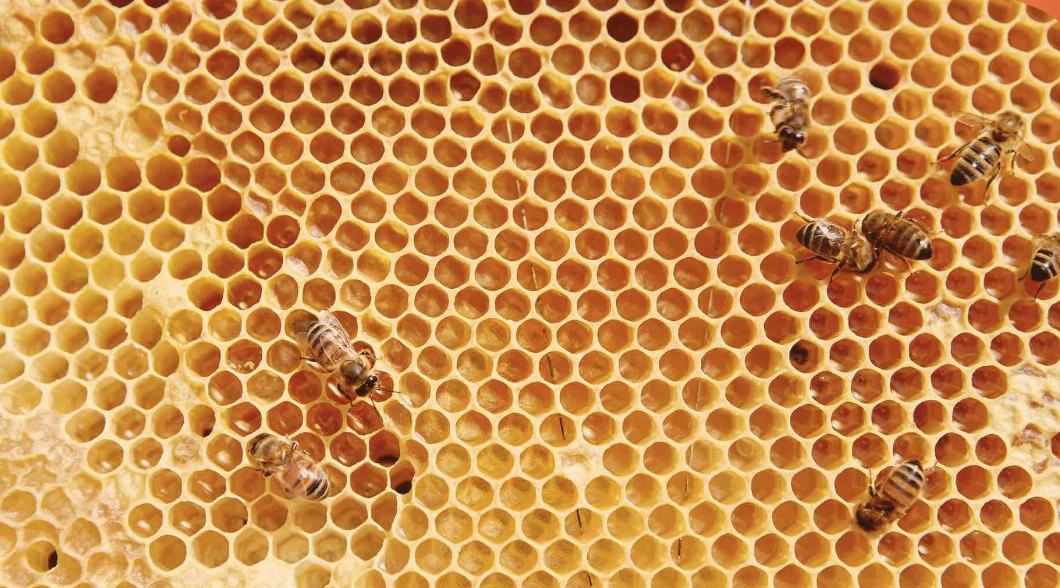

In an ever-changing threat landscape, security vendors around the world are forced to quickly adapt, react, and respond to known attack vectors and threats. In the face of this, malicious actors are constantly looking for novel ways to gain access to networks. Whether that’s through new exploitations of network vulnerabilities or new delivery methods, attackers and their methods are continually evolving. Although it is valuable for organizations to leverage threat intelligence to keep abreast of known threats to their networks, intelligence alone is not enough to defend against increasingly versatile attackers. Having an autonomous decision maker able to detect and respond to emerging threats, even those employing novel or unknown techniques, is paramount to defend against network compromise.

At the end of January 2023, threat actors began to abuse OneNote attachments to deliver the malware strain, Qakbot, onto users' devices. Widespread adoption of this novel delivery method resulted in a surge in Qakbot infections across Darktrace's customer base between the end of January 2023 and the end of February 2023. Using its Self-Learning AI, Darktrace was able to uncover and respond to these so-called ‘QakNote’ infections as the new trend emerged. Darktrace detected and responded to the threat at multiple stages of the kill chain, preventing damaging and widespread compromise to customer networks.

Qakbot and The Recent Weaponization of OneNote

Qakbot first appeared in 2007 as a banking trojan designed to steal sensitive data such as banking credentials. Since then, Qakbot has evolved into a highly modular, multi-purpose tool, with backdoor, payload delivery, reconnaissance, lateral movement, and data exfiltration capabilities. Although Qakbot's primary delivery method has always been email-based, threat actors have been known to modify their email-based delivery methods of Qakbot in the face of changing circumstances. In the first half of 2022, Microsoft started rolling out versions of Office which block XL4 and VBA macros by default [1]/[2]/[3]. Prior to this change, Qakbot email campaigns typically consisted in the spreading of deceitful emails with Office attachments containing malicious macros. In the face of Microsoft's default blocking of macros, threat actors appeared to cease delivering Qakbot via Office attachments, and shifted to primarily using HTML attachments, through a method known as 'HTML smuggling' [4]/[5]. After the public disclosure [6] of the Follina vulnerability (CVE-2022-30190) in Microsoft Support Diagnostic Tool (MSDT) in May 2022, Qakbot actors were seen capitalizing on the vulnerability to facilitate their email-based delivery of Qakbot payloads [7]/[8]/[9].

Given the inclination of Qakbot actors to adapt their email-based delivery methods, it is no surprise that they were quick to capitalize on the novel OneNote-based delivery method which emerged in December 2022. Since December 2022, threat actors have been seen using OneNote attachments to deliver a variety of malware strains, ranging from Formbook [10] to AsynRAT [11] to Emotet [12]. The abuse of OneNote documents to deliver malware is made possible by the fact that OneNote allows for the embedding of executable file types such as HTA files, CMD files, and BAT files. At the end of January 2023, actors started to leverage OneNote attachments to deliver Qakbot [13]/[14]. The adoption of this novel delivery method by Qakbot actors resulted in a surge in Qakbot infections in the wider threat landscape and across the Darktrace customer base.

Observed Activity Chains

Between January 31 and February 24, 2023, Darktrace observed variations of the following pattern of activity across its customer base:

1. User's device contacts OneNote-related endpoint

2. User's device makes an external GET request with an empty Host header, a target URI whose final segment consists in 5 or 6 digits followed by '.dat', and a User-Agent header referencing either cURL or PowerShell. The GET request is responded to with a DLL file

3. User's device makes SSL connections over ports 443 and 2222 to unusual external endpoints, and makes TCP connections over port 65400 to 23.111.114[.]52

4. User's device makes SSL connections over port 443 to an external host named 'bonsars[.]com' (IP: 194.165.16[.]56) and TCP connections over port 443 to 78.31.67[.]7

5. User’s device makes call to Endpoint Mapper service on internal systems and then connects to the Service Control Manager (SCM)

6. User's device uploads files with algorithmically generated names and ‘.dll’ or ‘.dll.cfg’ file extensions to SMB shares on internal systems

7. User's device makes Service Control requests to the systems to which it uploaded ‘.dll’ and ‘.dll.cfg’ files

Further investigation of these chains of activity revealed that they were parts of Qakbot infections initiated via interactions with malicious OneNote attachments.

Delivery Phase

Users' interactions with malicious OneNote attachments, which were evidenced by devices' HTTPS connections to OneNote-related endpoints, such as 'www.onenote[.]com', 'contentsync.onenote[.]com', and 'learningtools.onenote[.]com', resulted in the retrieval of Qakbot DLLs from unusual, external endpoints. In some cases, the user's interaction with the malicious OneNote attachment caused their device to fetch a Qakbot DLL using cURL, whereas, in other cases, it caused their device to download a Qakbot DLL using PowerShell. These different outcomes reflected variations in the contents of the executable files embedded within the weaponized OneNote attachments. In addition to having cURL and PowerShell User-Agent headers, the HTTP requests triggered by interaction with these OneNote attachments had other distinctive features, such as empty host headers and target URIs whose last segment consists in 5 or 6 digits followed by '.dat'.

Command and Control Phase

After fetching Qakbot DLLs, users’ devices were observed making numerous SSL connections over ports 443 and 2222 to highly unusual, external endpoints, as well as large volumes of TCP connections over port 65400 to 23.111.114[.]52. These connections represented Qakbot-infected devices communicating with command and control (C2) infrastructure. Qakbot-infected devices were also seen making intermittent connections to legitimate endpoints, such as 'xfinity[.]com', 'yahoo[.]com', 'verisign[.]com', 'oracle[.]com', and 'broadcom[.]com', likely due to Qakbot making connectivity checks.

Cobalt Strike and VNC Phase

After Qakbot-infected devices established communication with C2 servers, they were observed making SSL connections to the external endpoint, bonsars[.]com, and TCP connections to the external endpoint, 78.31.67[.]7. The SSL connections to bonsars[.]com were C2 connections from Cobalt Strike Beacon, and the TCP connections to 78.31.67[.]7 were C2 connections from Qakbot’s Virtual Network Computing (VNC) module [15]/[16]. The occurrence of these connections indicate that actors leveraged Qakbot infections to drop Cobalt Strike Beacon along with a VNC payload onto infected systems. The deployment of Cobalt Strike and VNC likely provided actors with ‘hands-on-keyboard’ access to the Qakbot-infected systems.

Lateral Movement Phase

After dropping Cobalt Strike Beacon and a VNC module onto Qakbot-infected systems, actors leveraged their strengthened foothold to connect to the Service Control Manager (SCM) on internal systems in preparation for lateral movement. Before connecting to the SCM, infected systems were seen making calls to the Endpoint Mapper service, likely to identify exposed Microsoft Remote Procedure Call (MSRPC) services on internal systems. The MSRPC service, Service Control Manager (SCM), is known to be abused by Cobalt Strike to create and start services on remote systems. Connections to this service were evidenced by OpenSCManager2 (Opnum: 0x40) and OpenSCManagerW (Opnum: 0xf) calls to the svcctl RPC interface.

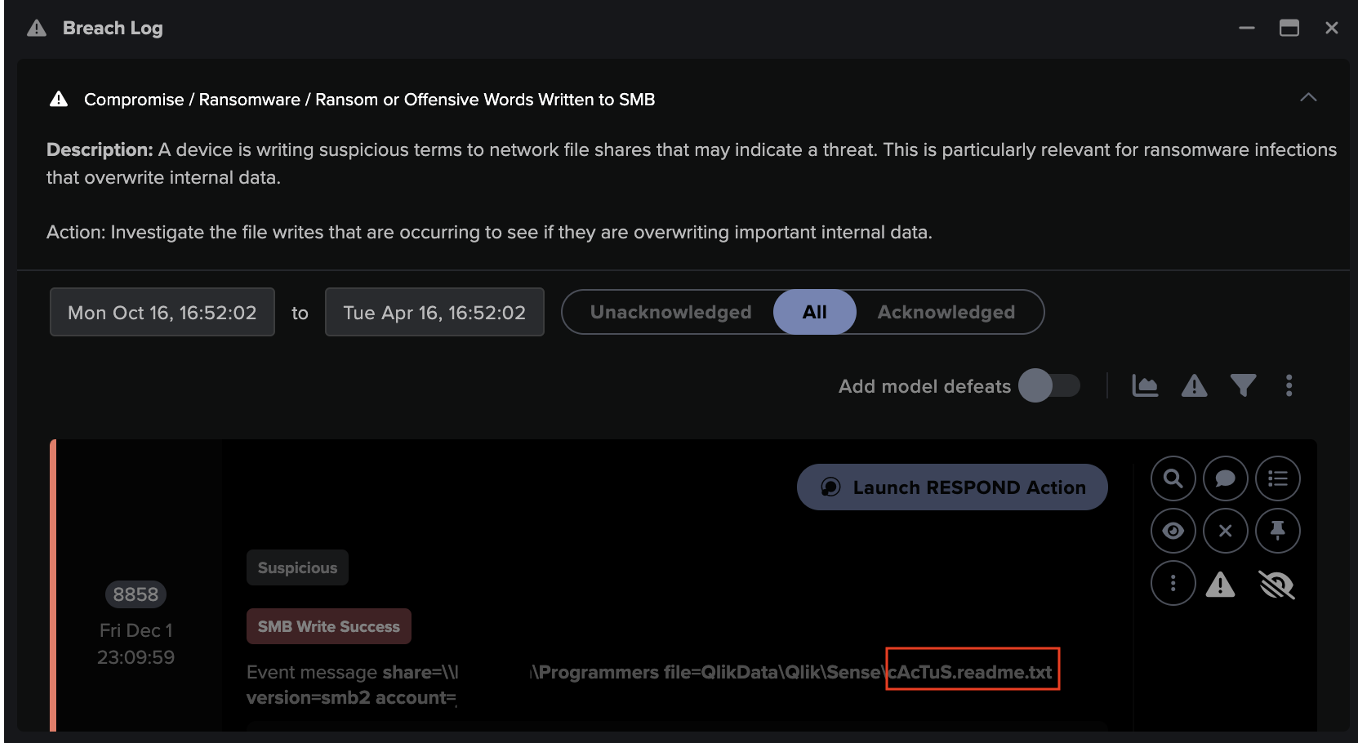

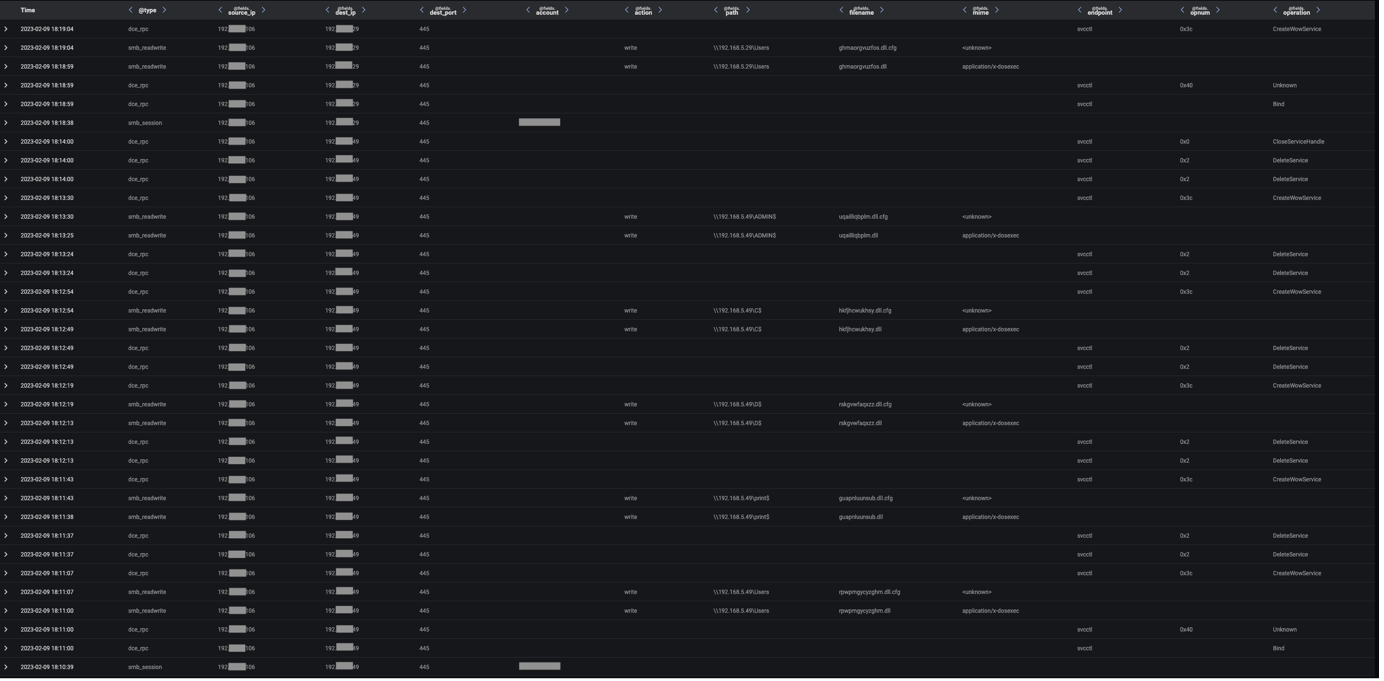

After connecting to the SCM on internal systems, infected devices were seen using SMB to distribute files with ‘.dll’ and ‘.dll.cfg’ extensions to SMB shares. These uploads were followed by CreateWowService (Opnum: 0x3c) calls to the svcctl interface, likely intended to execute the uploaded payloads. The naming conventions of the uploaded files indicate that they were Qakbot payloads.

Fortunately, none of the observed QakNote infections escalated further than this. If these infections had escalated, it is likely that they would have resulted in the widespread detonation of additional malicious payloads, such as ransomware.

Darktrace Coverage of QakNote Activity

Figure 1 shows the steps involved in the QakNote infections observed across Darktrace’s customer base. How far attackers got along this chain was in part determined by the following three factors:

- Whether the targeted customer had Darktrace/Email

- Whether the targeted customer had Darktrace RESPOND/Network

- Whether the targeted customer acted in response to Darktrace DETECT/Network alerts

The presence of Darktrace/Email typically stopped QakNote infections from moving past the initial infection stage. The presence of RESPOND/Network significantly slowed down observed activity chains, however, infections left unattended and not mitigated by the security teams were able to progress further along the attack chain.

Darktrace observed varying properties in the QakNote emails detected across the customer base. OneNote attachments were typically detected as either ‘application/octet-stream’ files or as ‘application/x-tar’ files. In some cases, the weaponized OneNote attachment embedded a malicious file, whereas in other cases, the OneNote file embedded a malicious link (typically a ‘.png’ or ‘.gif’ link) instead. In all cases Darktrace observed, QakNote emails used subject lines starting with ‘RE’ or ‘FW’ to manipulating their recipients into thinking that such emails were part of an existing email chain/thread. In some cases, emails impersonated users known to their recipients by including the names of such users in their header-from personal names. In many cases, QakNote emails appear to have originated from likely hijacked email accounts. These are highly successful methods of social engineering often employed by threat actors to exploit a user’s trust in known contacts or services, convincing them to open malicious emails and making it harder for security tools to detect.

The fact that observed QakNote emails used the fake-reply method, were sent from unknown email accounts, and contained attachments with unusual MIME types, caused such emails to breach the following Darktrace/Email models:

- Association / Unknown Sender

- Attachment / Unknown File

- Attachment / Unsolicited Attachment

- Attachment / Highly Unusual Mime

- Attachment / Unsolicited Anomalous Mime

- Attachment / Unusual Mime for Organisation

- Unusual / Fake Reply

- Unusual / Unusual Header TLD

- Unusual / Fake Reply + Unknown Sender

- Unusual / Unusual Connection from Unknown

- Unusual / Off Topic

QakNote emails impersonating known users also breached the following DETECT & RESPOND/Email models:

- Unusual / Unrelated Personal Name Address

- Spoof / Basic Known Entity Similarities

- Spoof / Internal User Similarities

- Spoof / External User Similarities

- Spoof / Internal User Similarities + Unrelated Personal Name Address

- Spoof / External User Similarities + Unrelated Personal Name Address

- Spoof / Internal User Similarities + Unknown File

- Spoof / External User Similarities + Fake Reply

- Spoof / Possible User Spoof from New Address - Enhanced Internal Similarities

- Spoof / Whale

The actions taken by Darktrace on the observed emails is ultimately determined by Darktrace/Email models are breached. Those emails which did not breach Spoofing models (due to lack of impersonation indicators) received the ‘Convert Attachment’ action. This action converts suspicious attachments into neutralized PDFs, in this case successfully unweaponizing the malicious OneNote attachments. QakNote emails which did breach Spoofing models (due to the presence of impersonation indicators) received the strongest possible action, ‘Hold Message’. This action prevents suspicious emails from reaching the recipients’ mailbox.

If threat actors managed to get past the first stage of the QakNote kill chain, likely due to the absence of appropriate email security tools, the execution of the subsequent steps resulted in strong intervention from Darktrace/Network.

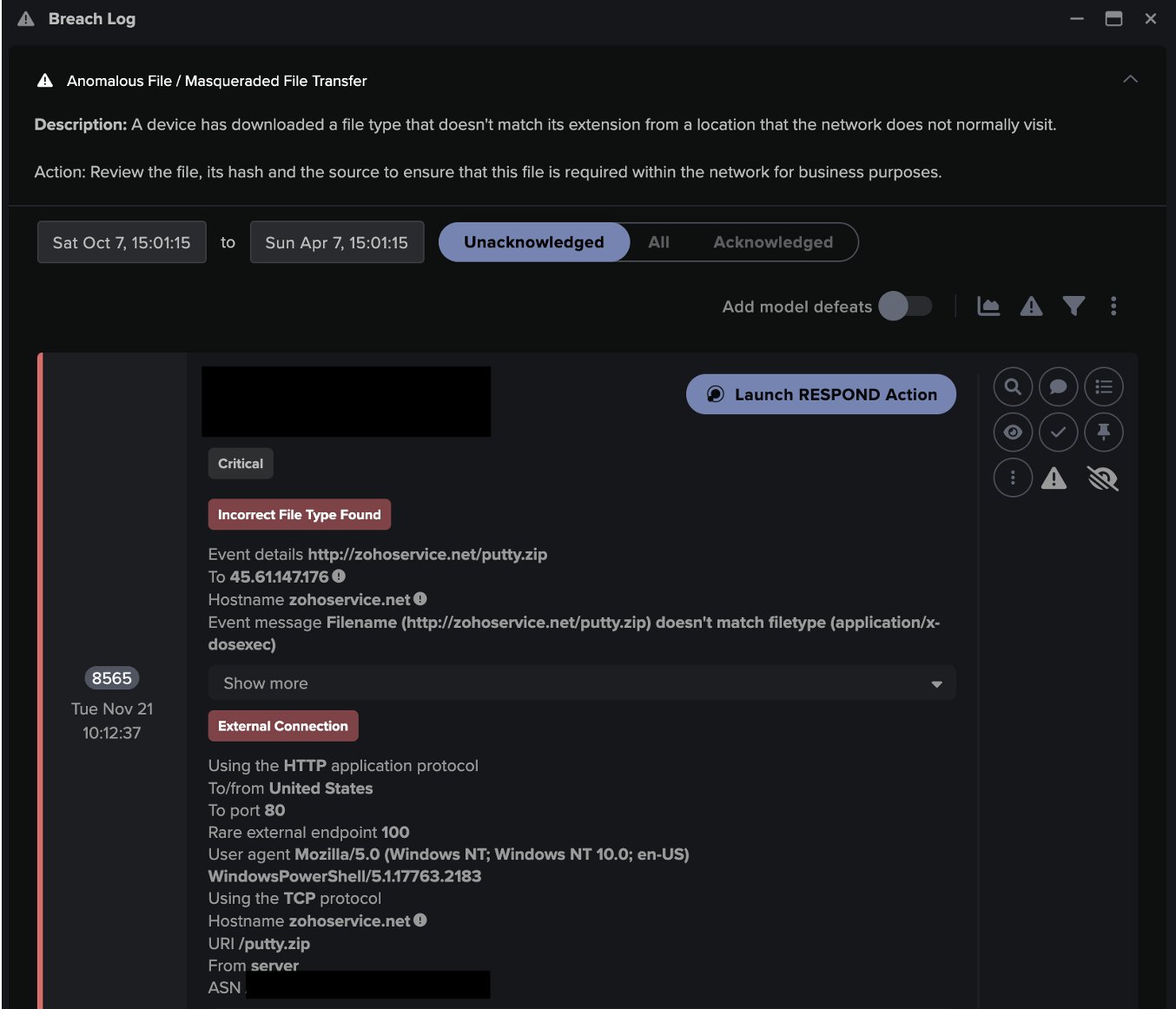

Interactions with malicious OneNote attachments caused their devices to fetch a Qakbot DLL from a remote server via HTTP GET requests with an empty Host header and either a cURL or PowerShell User-Agent header. These unusual HTTP behaviors caused the following Darktrace/Network models to breach:

- Device / New User Agent

- Device / New PowerShell User Agent

- Device / New User Agent and New IP

- Anomalous Connection / New User Agent to IP Without Hostname

- Anomalous Connection / Powershell to Rare External

- Anomalous File / Numeric File Download

- Anomalous File / EXE from Rare External Location

- Anomalous File / New User Agent Followed By Numeric File Download

For customers with RESPOND/Network active, these breaches resulted in the following autonomous actions:

- Enforce group pattern of life for 30 minutes

- Enforce group pattern of life for 2 hours

- Block connections to relevant external endpoints over relevant ports for 2 hours

- Block all outgoing traffic for 10 minutes

Successful, uninterrupted downloads of Qakbot DLLs resulted in connections to Qakbot C2 servers, and subsequently to Cobalt Strike and VNC C2 connections. These C2 activities resulted in breaches of the following DETECT/Network models:

- Compromise / Suspicious TLS Beaconing To Rare External

- Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Successful Connections

- Compromise / Large Number of Suspicious Failed Connections

- Compromise / Sustained SSL or HTTP Increase

- Compromise / Sustained TCP Beaconing Activity To Rare Endpoint

- Compromise / Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Compromise / Slow Beaconing Activity To External Rare

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Connections to New External TCP Port

- Anomalous Connection / Multiple Failed Connections to Rare Endpoint

- Device / Initial Breach Chain Compromise

For customers with RESPOND/Network active, these breaches caused RESPOND to autonomously perform the following actions:

- Block connections to relevant external endpoints over relevant ports for 1 hour

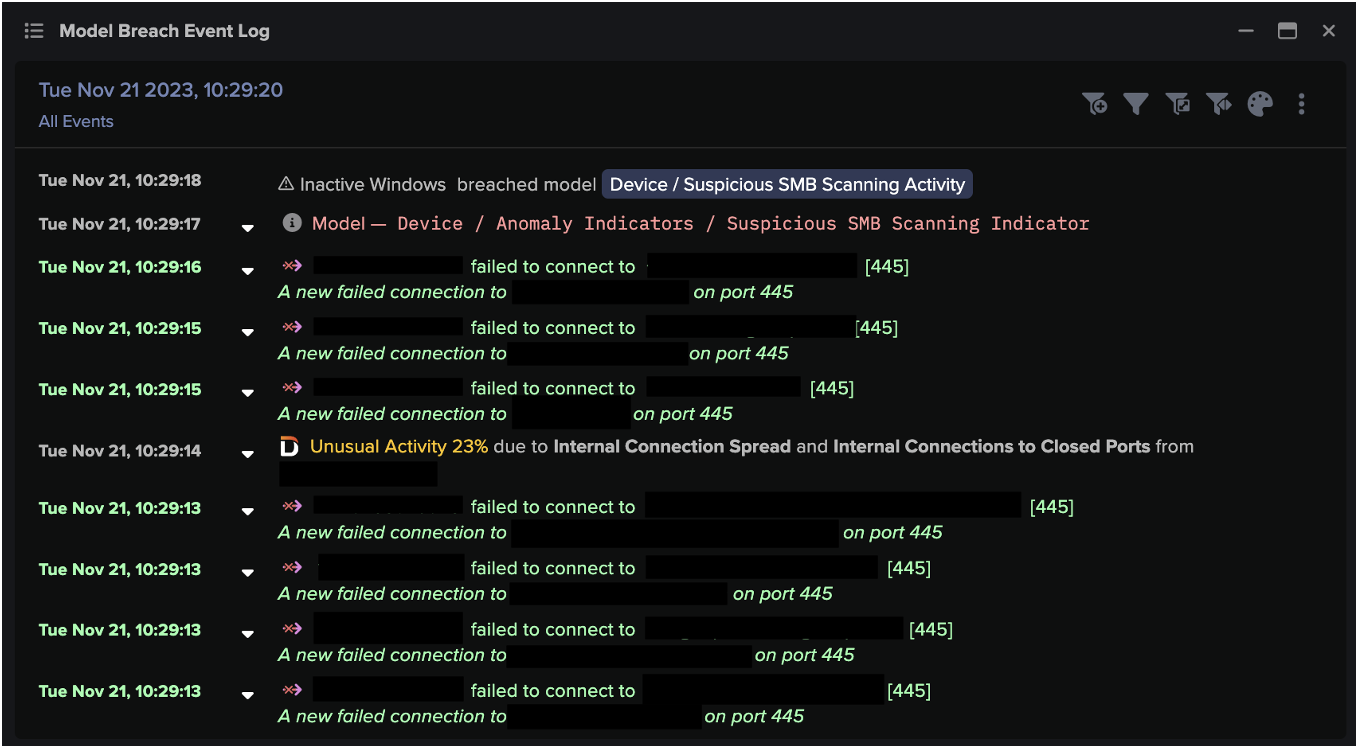

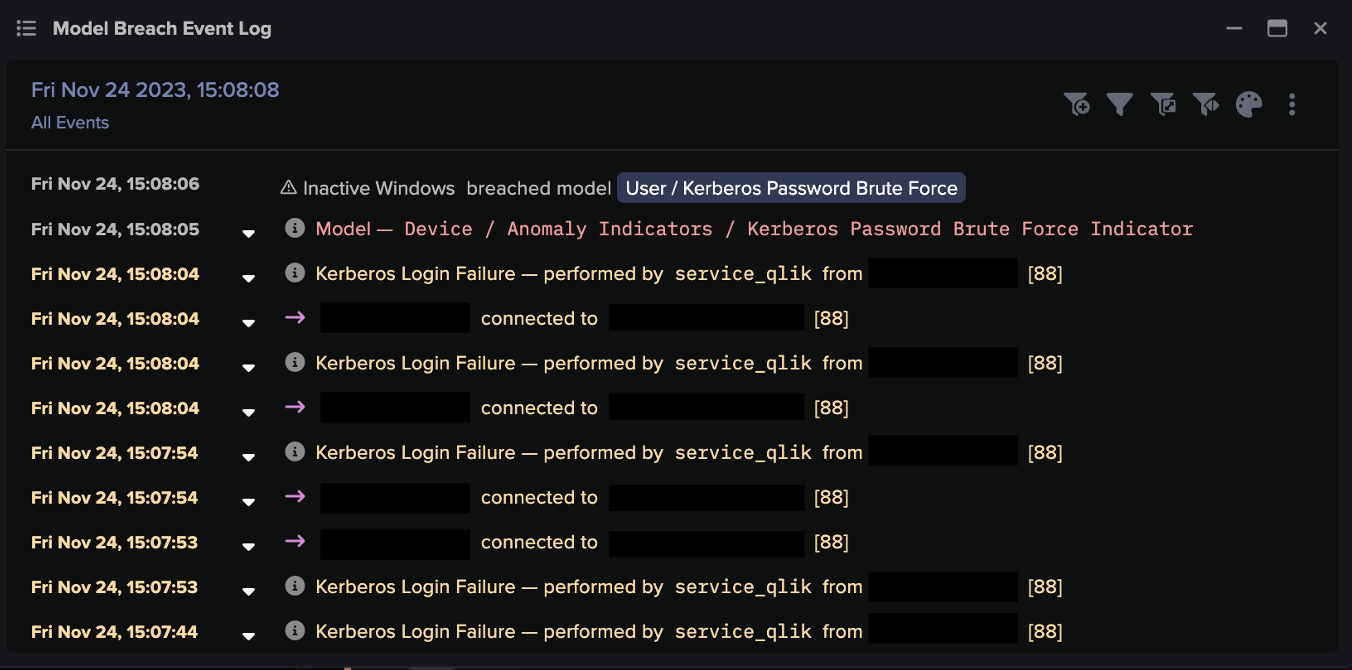

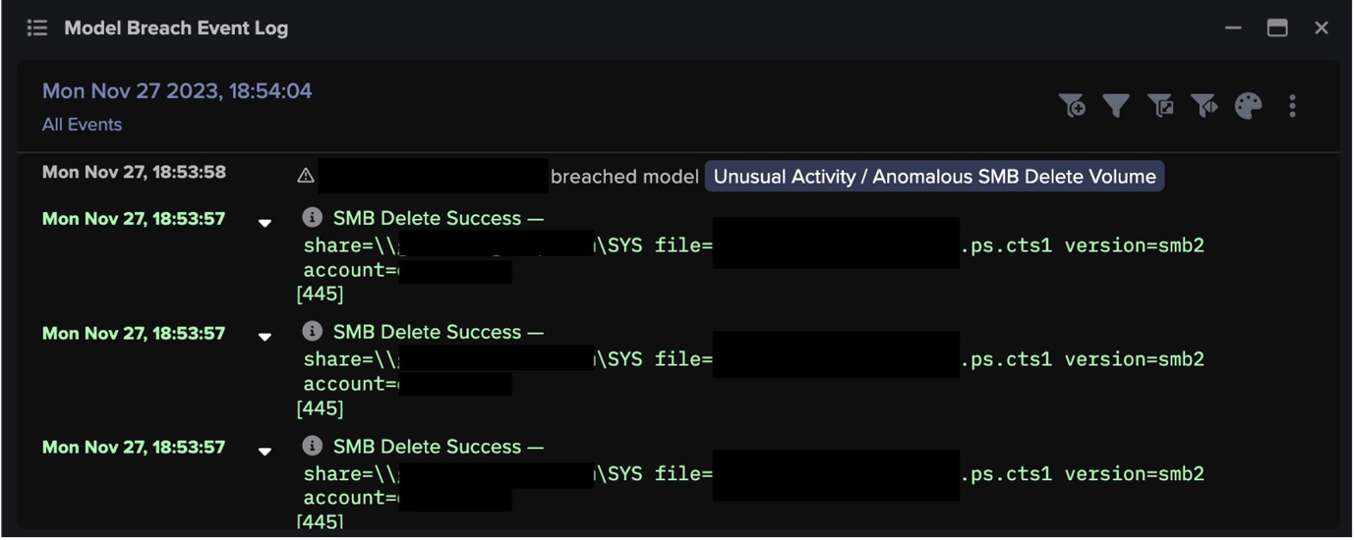

In cases where C2 connections were allowed to continue, actors attempted to move laterally through usage of SMB and Service Control Manager. This lateral movement activity caused the following DETECT/Network models to breach:

- Device / Possible SMB/NTLM Reconnaissance

- Anomalous Connection / New or Uncommon Service Control

For customers with RESPOND/Network enabled, these breaches caused RESPOND to autonomously perform the following actions:

- Block connections to relevant internal endpoints over port 445 for 1 hour

The QakNote infections observed across Darktrace’s customer base involved several steps, each of which elicited alerts and autonomous preventative actions from Darktrace. By autonomously investigating the alerts from DETECT, Darktrace’s Cyber AI Analyst was able to connect the distinct steps of observed QakNote infections into single incidents. It then produced incident logs to present in-depth details of the activity it uncovered, provide full visibility for customer security teams.

Conclusion

Faced with the emerging threat of QakNote infections, Darktrace demonstrated its ability to autonomously detect and respond to arising threats in a constantly evolving threat landscape. The attack chains which Darktrace observed across its customer base involved the delivery of Qakbot via malicious OneNote attachments, the usage of ports 65400 and 2222 for Qakbot C2 communication, the usage of Cobalt Strike Beacon and VNC for ‘hands-on-keyboard’ activity, and the usage of SMB and Service Control Manager for lateral movement.

Despite the novelty of the OneNote-based delivery method, Darktrace was able to identify QakNote infections across its customer base at various stages of the kill chain, using its autonomous anomaly-based detection to identify unusual activity or deviations from expected behavior. When active, Darktrace/Email neutralized malicious QakNote attachments sent to employees. In cases where Darktrace/Email was not active, Darktrace/Network detected and slowed down the unusual network activities which inevitably ensued from Qakbot infections. Ultimately, this intervention from Darktrace’s products prevented infections from leading to further harmful activity, such as data exfiltration and the detonation of ransomware.

Darktrace is able to offer customers an unparalleled level of network security by combining both Darktrace/Network and Darktrace/Email, safeguarding both their email and network environments. With its suite of products, including DETECT and RESPOND, Darktrace can autonomously uncover threats to customer networks and instantaneously intervene to prevent suspicious activity leading to damaging compromises.

Appendices

MITRE ATT&CK Mapping

Initial Access:

T1566.001 – Phishing: Spearphishing Attachment

Execution:

T1204.001 – User Execution: Malicious Link

T1204.002 – User Execution: Malicious File

T1569.002 – System Services: Service Execution

Lateral Movement:

T1021.002 – Remote Services: SMB/Windows Admin Shares

Command and Control:

T1573.002 – Encrypted Channel : Asymmetric Cryptography

T1571 – Non-Standard Port

T1105 – Ingress Tool Transfer

T1095 – Non-Application Layer Protocol

T1219 – Remote Access Software

List of IOCs

IP Addresses and/or Domain Names:

- 103.214.71[.]45 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 141.164.35[.]94 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 95.179.215[.]225 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 128.254.207[.]55 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 141.164.35[.]94 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 172.96.137[.]149 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 185.231.205[.]246 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 216.128.146[.]67 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 45.155.37[.]170 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 85.239.41[.]55 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 45.67.35[.]108 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 77.83.199[.]12 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 45.77.63[.]210 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 198.44.140[.]78 - Qakbot download infrastructure

- 47.32.78[.]150 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 197.204.13[.]52 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 68.108.122[.]180 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 2.50.48[.]213 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 66.180.227[.]60 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 190.206.75[.]58 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 109.150.179[.]236 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 86.202.48[.]142 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 143.159.167[.]159 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 5.75.205[.]43 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 184.176.35[.]223 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 208.187.122[.]74 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 23.111.114[.]52 - Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- 74.12.134[.]53 – Qakbot C2 infrastructure

- bonsars[.]com • 194.165.16[.]56 - Cobalt Strike C2 infrastructure

- 78.31.67[.]7 - VNC C2 infrastructure

Target URIs of GET Requests for Qakbot DLLs:

- /70802.dat

- /51881.dat

- /12427.dat

- /70136.dat

- /35768.dat

- /41981.dat

- /30622.dat

- /72286.dat

- /46557.dat

- /33006.dat

- /300332.dat

- /703558.dat

- /760433.dat

- /210/184/187737.dat

- /469/387/553748.dat

- /282/535806.dat

User-Agent Headers of GET Requests for Qakbot DLLs:

- curl/7.83.1

- curl/7.55.1

- Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; en-US) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.19041.2364

- Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; en-US) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.17763.3770

- Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT; Windows NT 10.0; en-GB) WindowsPowerShell/5.1.19041.2364

SHA256 Hashes of Downloaded Qakbot DLLs:

- 83e9bdce1276d2701ff23b1b3ac7d61afc97937d6392ed6b648b4929dd4b1452

- ca95a5dcd0194e9189b1451fa444f106cbabef3558424d9935262368dba5f2c6

- fa067ff1116b4c8611eae9ed4d59a19d904a8d3c530b866c680a7efeca83eb3d

- e6853589e42e1ab74548b5445b90a5a21ff0d7f8f4a23730cffe285e2d074d9e

- d864d93b8fd4c5e7fb136224460c7b98f99369fc9418bae57de466d419abeaf6

- c103c24ccb1ff18cd5763a3bb757ea2779a175a045e96acbb8d4c19cc7d84bea

Names of Internally Distributed Qakbot DLLs:

- rpwpmgycyzghm.dll

- rpwpmgycyzghm.dll.cfg

- guapnluunsub.dll

- guapnluunsub.dll.cfg

- rskgvwfaqxzz.dll

- rskgvwfaqxzz.dll.cfg

- hkfjhcwukhsy.dll

- hkfjhcwukhsy.dll.cfg

- uqailliqbplm.dll

- uqailliqbplm.dll.cfg

- ghmaorgvuzfos.dll

- ghmaorgvuzfos.dll.cfg

Links Found Within Neutralized QakNote Email Attachments:

- hxxps://khatriassociates[.]com/MBt/3.gif

- hxxps://spincotech[.]com/8CoBExd/3.gif

- hxxps://minaato[.]com/tWZVw/3.gif

- hxxps://famille2point0[.]com/oghHO/01.png

- hxxps://sahifatinews[.]com/jZbaw/01.png

- hxxp://87.236.146[.]112/62778.dat

- hxxp://87.236.146[.]112/59076.dat

- hxxp://185.231.205[.]246/73342.dat

References

[1] https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/excel-blog/excel-4-0-xlm-macros-now-restricted-by-default-for-customer/ba-p/3057905

[2] https://techcommunity.microsoft.com/t5/microsoft-365-blog/helping-users-stay-safe-blocking-internet-macros-by-default-in/ba-p/3071805

[3] https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/deployoffice/security/internet-macros-blocked

[4] https://www.cyfirma.com/outofband/html-smuggling-a-stealthier-approach-to-deliver-malware/

[5] https://www.trustwave.com/en-us/resources/blogs/spiderlabs-blog/html-smuggling-the-hidden-threat-in-your-inbox/

[6] https://twitter.com/nao_sec/status/1530196847679401984

[7] https://www.fortiguard.com/threat-signal-report/4616/qakbot-delivered-through-cve-2022-30190-follina

[8] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/rss/28728

[9] https://darktrace.com/blog/qakbot-resurgence-evolving-along-with-the-emerging-threat-landscape

[10] https://www.trustwave.com/en-us/resources/blogs/spiderlabs-blog/trojanized-onenote-document-leads-to-formbook-malware/

[11] https://www.proofpoint.com/uk/blog/threat-insight/onenote-documents-increasingly-used-to-deliver-malware

[12] https://www.malwarebytes.com/blog/threat-intelligence/2023/03/emotet-onenote

[13] https://blog.cyble.com/2023/02/01/qakbots-evolution-continues-with-new-strategies/

[14] https://news.sophos.com/en-us/2023/02/06/qakbot-onenote-attacks/

[15] https://isc.sans.edu/diary/rss/29210

[16] https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/feb-wireshark-quiz-answers/

![Cyber AI Analyst Incident Log showing the offending device making over 1,000 connections to the suspicious hostname “zohoservice[.]net” over port 8383, within a specific period.](https://assets-global.website-files.com/626ff4d25aca2edf4325ff97/662971c1cf09890fd46729a1_Screenshot%202024-04-24%20at%201.55.10%20PM.png)